Sydney University turns visa factory

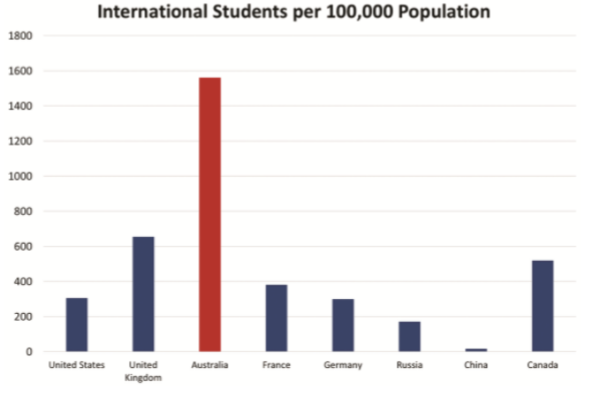

Before the pandemic, Australia had by far the highest concentration of international students in the world, dwarfing other Anglo nations:

Source: Salvatore Babones (2019)

The explosion in student numbers followed the strategic review of the student visa program in 2011 (‘the Knight review’) by the Gillard Government, which greatly expanded work rights for graduate (485) visas in 2013.

In particular, 485 visa holders were not required to meet skills shortage requirements. They were permitted to remain in Australia for two to four years after completing their studies rather than the previous 18 months.

The Knight review was strongly in favour of expanding post-study work rights (PSWR) because it would greatly increase Australia’s attractiveness as a destination for international students, in turn benefiting Australian universities and employers.

The result was that international education was quickly turned into an immigration industry. Australia’s graduate (485) visas are considered among the most attractive in the world because they provide full work rights. They are also highly valued by international students because they are perceived as a pathway to permanent residency.

As Peter Mares explained:

Knight stated plainly that an expanded work visa was essential to “the ongoing viability of our universities in an increasingly competitive global market for students.”

Vice-chancellors also made the connection explicit. At the time, Glenn Withers, chief executive of Universities Australia, said that Knight’s “breakthrough” proposal was as good as or better than the work rights on offer in Canada and the United States.

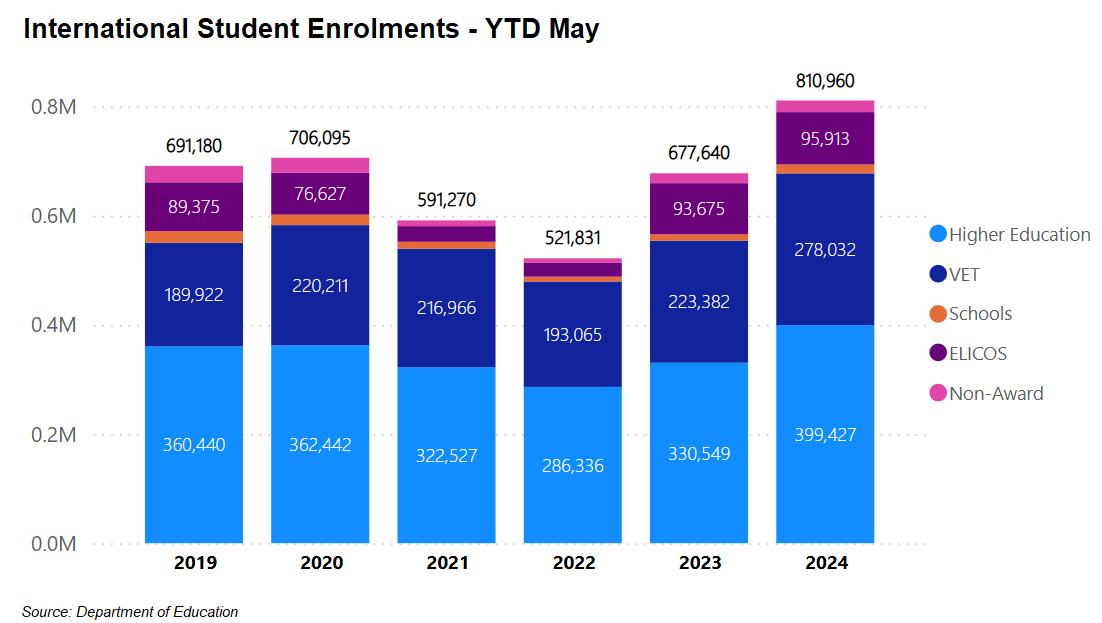

The concentration of international students studying in Australia has increased following the pandemic, given that there are now 811,000 international students enrolled in Australia versus 691,200 in 2019:

According to Department of Home Affairs visa data, nearly one-in-30 people in Australia currently are on either a student visa or graduate visa – a startling figure.

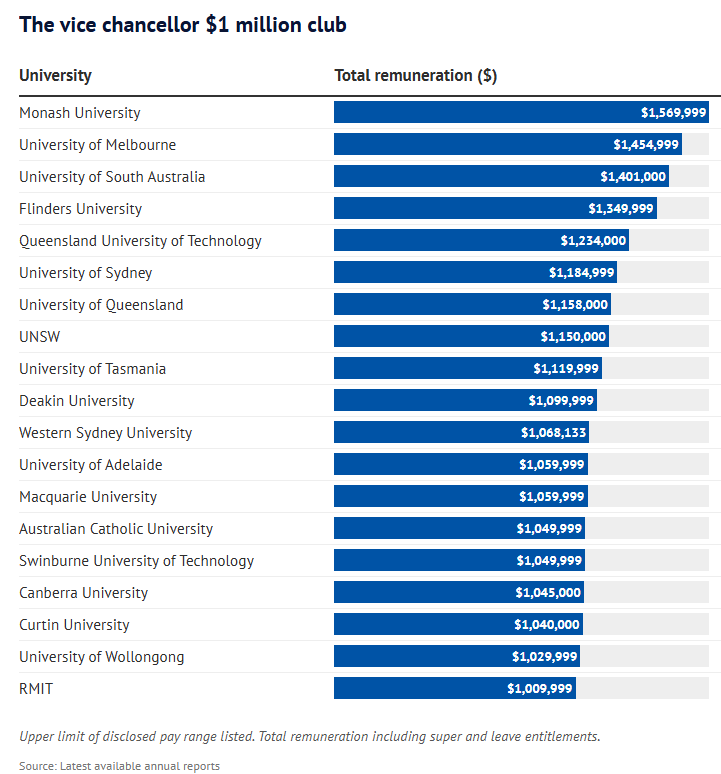

This extreme concentration of international students has delivered the highest paid university vice-chancellors in the world, with salaries of more than $1 million commonplace:

At the same time, universities have been mired in staff underpayment scandals, cheating in rife, and academic staff have been prohibited from failing poor performing international students because it risks the ‘churn and burn’ business model:

The concentration of international students is so high that some tutorials have even been conducted in Mandarin, thereby excluding local students from discussion:

Despite these inconvenient truths, the federal government’s proposal to cap international student enrolments at 40% has been met with furious opposition from the education lobby.

But even a 40% cap is ridiculously high and would leave Australia with easily the highest concentration of international students in the world.

By way of comparison, the single most internationalised public university in the entire United States, the University of Illinois, has only 23% international students.

Really, a 40% cap on international enrolments is around double what it should be if maintaining academic integrity and teaching quality is the goal.

With this background in mind, it was disturbing to read that international enrolments at Sydney University have hit “around 50%”:

Scott said the university’s senate had in 2021 determined that about 50% should be the ceiling for the proportion of international students at the institution, which is heavily reliant on Chinese enrolments…

“I don’t think there is a magic number here,” he said. “I don’t think social licence disappears suddenly when you pass a certain threshold.”

Anyone with half a brain would recognise that vested interests have contaminated higher education in Australia.

Australian universities once existed to provide education to young Australians. Now they are more interested in maximising fee revenue from international students.

Australia must aim for a significantly lower number of high-quality students. Caps should be set to 20%, not 40%.

Higher education must prioritise quality over quantity and pedagogical standards over revenue.

Comments

Post a Comment