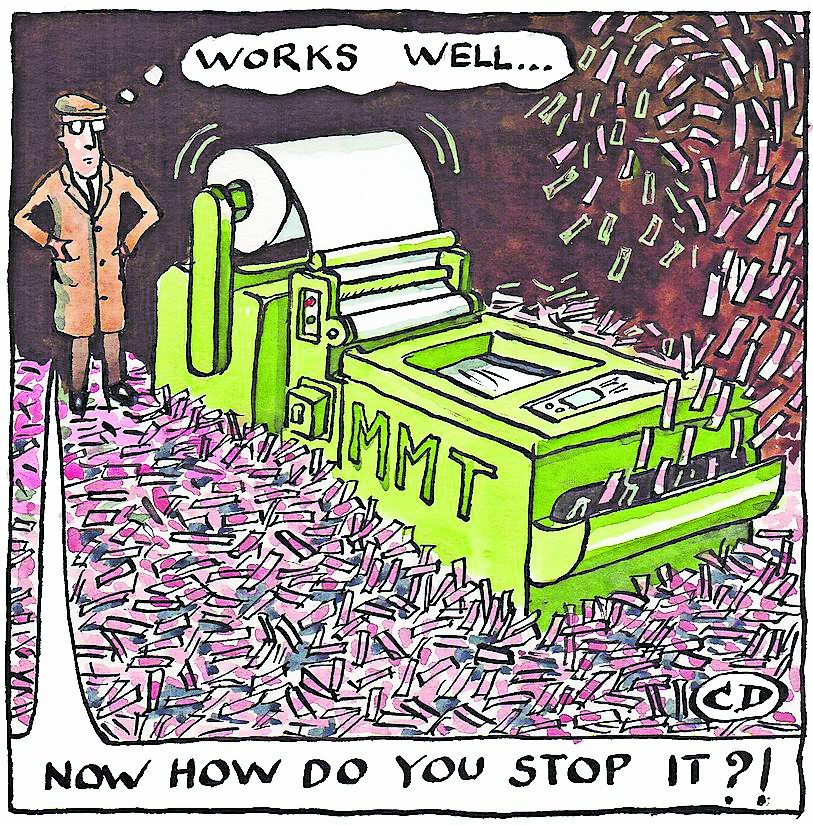

Printing money sounds like a good idea until reality comes to the party

"Everyone likes more public services and higher government spending as long as they are not the ones paying for it. As George Bernard Shaw put it in 1944, a government that robs Peter to pay Paul can always count on the support of Paul.

Why should politicians not take this idea to its logical conclusion? What if neither Peter nor Paul had to pay, and you could snaffle both their votes? What if the Treasury could simply print as much money as it wanted to pay for whatever we needed?

That might sound mad, but it is an old idea that is coming back into vogue thanks to Zack Polanski, the leader of the Green Party. He has said the government shouldn’t worry about the gilts market and the Bank of England’s balance sheet is “money we owe to ourselves”.

As Matthew Parris pointed out on Wednesday, all kinds of people love Polanski’s fresh approach. It may, however, be about to be reined in a little. A new think tank linked to the party, Verdant, is expected to launch next year, with the aim of bringing some cohesiveness and rigour to the movement’s economic policies.

Polanski, it must be said, has not gone all-in on the money-printing plan: he supports other ideas too, notably hefty wealth taxes.

These unorthodox economics ring a bell with me. I grew up in New Zealand in the 1970s when Social Credit, a party with radical ideas, was on the rise. Social Credit took 20 per cent of the vote in the 1981 election, thanks largely to the personal popularity of its leader, Bruce Beetham, who, like Polanksi, was an excellent communicator. These kinds of policies have had more recent surges in popularity, and in larger economies.

They became fashionable on the left of United States politics about five years ago thanks to Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, one of the bestselling business books of 2020.

Kelton, an economics professor at Stony Brook University on Long Island, was an adviser to Bernie Sanders, who ran against Joe Biden for the Democratic presidential nomination the same year. Modern monetary theory draws on the work of economists going back more than a century. There are two basic ideas.

The first is that governments cannot go bust, because they have the sovereign right to print money. The second is that government spending and taxation can be regulated to control inflation and employment.

Spend when there is a slump, with high unemployment and low inflation, and pull back when the economy heats up. (There is a lot more to it than that, including a job guarantee programme.)

It is worth saying, as my colleague David Smith did when he wrote about Kelton’s book, that talking about modern monetary theory risks a torrent of personal criticism. It is a bit like cryptocurrencies, you are either a total idiot for giving any space to the subject or a total idiot for questioning the obvious rightness of the cause.

If you are not a total idiot, then you are certainly in the pay of the billionaire elite/big banks/illuminati who are working together to suppress the truth. No doubt lots of that is headed my way. It would be wrong, though, immediately to dismiss ideas that stray from the orthodox. One of the lessons of Martin Slater’s excellent history of British government borrowing, The National Debt, published in 2018, is that there have been many approaches to this issue over the past 300 years. Policies have changed as fast as politics itself and the accepted wisdom of how to deal with borrowing just a few decades ago would now be regarded as anathema. Policies will continue to change and our future selves will no doubt look back at some current ideas with scorn.

The other thing pushing modern monetary theory and its variants to the front of the debate is that they don’t look much different to what western governments have been doing for the past two decades.

The Federal Reserve and the Bank of England both printed money (not literally, they allowed more money into the system by buying assets from banks and other financial institutions) to stimulate the economy. They started in response to the banking crisis of 2007 and then really splurged during the Covid-19 pandemic. Over the two interventions the Bank of England bought £895 billion worth of bonds, almost all of them gilts. At one point the Bank owned just over a third of all government debt. The problem with modern monetary theory, however, is that moneyprinting can easily run out of control, with dire consequences.

As Rachel Reeves is discovering, cutting government spending is hard, particularly when you have a large number of MPs who think keeping it going, and even expanding it, is their one route to political survival. The idea that a government elected on a modern monetary theory manifesto would be able to curtail spending stretches belief.

There is another problem. The theory requires the right conditions to work, including low government debt to start and not too great a reliance on imports. How you create those conditions in Britain, which has lots of debt and a persistent goods deficit, is difficult to fathom. Its acolytes should also look at the many demonstrations of how expansion of the money supply works in practice.

Argentina never practised modern monetary theory but it did have governments that were happy to run deficits and print money to keep the electorate on side. The end result was runaway inflation and a backlash that catapulted Javier Milei to power.

Something similar happened in New Zealand. It too struggled with bouts of high inflation and in the end embraced not the radicalism of Social Credit but a way of taking the moneyprinting button further out of politicians’ reach. It made its central bank independent in 1989 and gave it the single job of controlling inflation.

The result was a tough recession and high unemployment for a couple of years and then a steady recovery. It was judged enough of a success for the model to be copied elsewhere, including in Britain eight years later.

When the economy is struggling and people struggle to make ends meet, radical solutions that promise an easy way out seem attractive. But remember, if someone offers you something that is too good to be true, it usually is."

Dominic O’Connell is business presenter for Times Radio

Comments

Post a Comment