Economics Nobel prize won by researchers who showed how science boosts growth

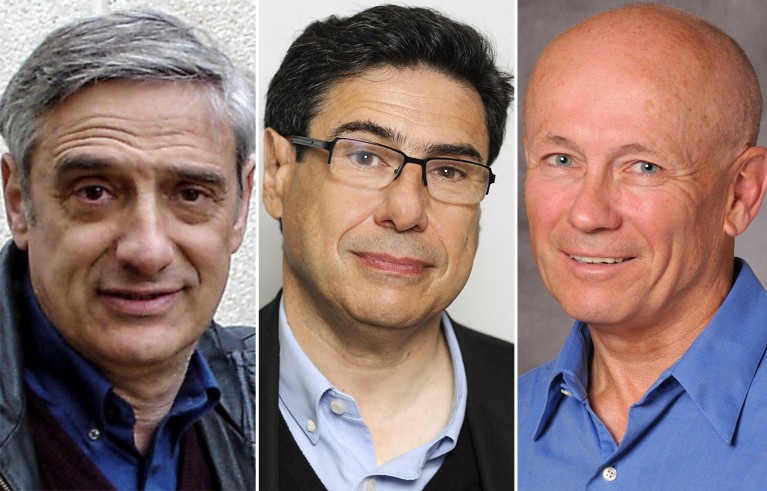

L to R: Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt.Credit: Northwestern University, Patrick Imbert/Collège de France, Ashley McCabe/Brown University

The 2025 Sveriges Riksbank Prize for Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel has been awarded to three researchers who have shown how technological and scientific innovation, coupled to market competition, drive economic growth.

One half of the prize goes to Joel Mokyr, an economic historian at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. The other half is split between the economic theorists Philippe Aghion at the Collège de France in Paris and the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Peter Howitt at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

“I can’t find the words to express what I feel,” Aghion told the press conference. He added that he will use the money for research in his laboratory at the Collège de France.

The award “underlies the importance in investing in science for innovation and long-term economic growth”, says economist Diane Coyle at the University of Cambridge, UK. “It’s great to see the Nobel prize recognize the importance of this topic,” adds Richard Jones, an innovation-policy researcher at the University of Manchester, UK. “It's important that economists understand the conditions that lead to technological progress,” he adds. The winners, says Coyle, “have long been on people’s list of potential candidates”.

Old isn’t gold

Economic growth at a rate of 1–2% annually is the norm for industrialized nations today. But such growth rates did not happen in pre-industrial times, despite technological innovations such as the windmill and the printing press.

Mokyr showed that the key difference between now and then was what he calls “useful knowledge”, or innovations based on scientific understanding1. One example is the advances during the Industrial Revolution, beginning in the eighteenth century, when improvements in steam engines could be made systematically rather than by trial and error.

Aghion and Howitt, for their part, clarified the market mechanisms behind sustained growth. In 1992, they presented a model showing how competition between companies selling new products allows innovations to enter the marketplace and displaces older products: a process they called creative destruction2.

Underlying growth, in other words, is a steady churn of businesses and products. The researchers showed how companies invest in research and development (R&D) to improve their chances of finding a new product, and predicted the optimal level of such investment.

Entrepreneurial state

According to Ufuk Akcigit, an economist at the University of Chicago in Illinois, Aghion and Howitt highlight an important aspect of economic growth, which is that spending on R&D does not by itself guarantee higher rates of growth: “Unless we replace inefficient firms from the economy, we cannot make space for newcomers with new ideas and better technologies.”

“When a new entrepreneur emerges, they have every incentive to come up with a radical new technology,” Akcigit says. “As soon as they become an incumbent, their incentive vanishes” and they no longer invest in R&D to drive innovation.

Thus, because companies cannot expect to remain at the forefront of innovation indefinitely, the incentive for investing in R&D coming from market forces alone declines as a company’s market share grows. To guarantee the societal benefits of constant innovation, the model suggests that it is in society’s interests for the state to subsidize R&D, so long as the return is not merely incremental improvements.

The work of all three laureates also acknowledges the complex social consequences of growth. In the early days of the Industrial Revolution, there were concerns about how mechanization would cause unemployment among manual workers — a worry echoed today with the increasing use of AI in place of human labour. But Mokyr showed that, in fact, early mechanization led to the creation of jobs.

Creative destruction, meanwhile, leads to companies failing and jobs being lost. Aghion and Howitt emphasized that society needs safety nets and constructive negotiation of conflicts to navigate such problems.

Their model “recognizes the messiness and complexity of how innovation happens in real economies”, says Coyle. “The idea that a country’s productivity level increases by companies going bust and new ones coming in is a difficult sell, but the evidence that that’s part of the mechanism is pretty strong.”

Timely message

This year’s award comes at a time when funding for scientific research is under threat in the United States and around the world. “It’s a very timely message when we’re seeing the United States undermining so much of its science base,” says Coyle. “I don’t welcome the protectionist wave in the US,” Aghion said. “Openness is a driver of growth. I see dark clouds accumulating.”

Economic historian Kerstin Enflo, a member of the Nobel economic-sciences committee, denied that the award was intended as a comment on the direction of US policies. “It is only about celebrating the work [the laureates] have done,” she said at the press conference.

Green growth

More recently, researchers are questioning the ‘growth at all costs’ narrative, not least because the pursuit of growth has led to environmental degradation, including global warming.

“How can we make sure we innovate greener?” Aghion asked. “Firms don’t spontaneously do this. So how can we redirect growth towards green?” Mokyr’s work showed that growth can sometimes be self-correcting, producing the innovations needed to solve such problems. But that is not a given and requires well-crafted policies to nurture innovation without promoting inequality and a lack of sustainability. “We need to harness the productivity potential and minimize the negative effects,” said Aghion.

Nature 646, 782-783 (2025)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03364-2

Comments

Post a Comment